My beloved cat Rey, my little sweet potato, has had a rough summer.

Not only did she get diagnosed with lymphoma at the end of June, but she also had a stroke, or at least a “stroke-like event,” shortly after. On the morning of July 4th, she couldn’t walk and her pupils were trembling. Luckily, she has made an almost complete recovery from the stroke (still a little tilt or tremor here and there) and has started cancer treatment. For the most part, she is back to her feisty self.

The week following her stroke, when she could barely walk a foot without falling over, I was a goddamn mess. I slept on the couch so I could watch her as much as possible and keep her from trying to jump on or off things. After work, all I could handle was watching the Great British Baking Show. On a good day, I baked some things myself. But mostly I just stared at my cat and made sure she was breathing.

It’s really hard to reconcile being so upset about my cat when I don’t have to worry about ICE snatching me, bombs dropping on my house, or not being able feed my family. I know I’m allowed to be upset and that everything is relative, but I guess it’s important to put things in perspective and be grateful.

There was even a silver lining to her mobility issues. We let her outside (under strict supervision) because she couldn’t really run or jump, and I think she liked it.

Now for something unrelated. The other night, I attended a lecture hosted by the Monhegan Museum on how artists have depicted Monhegan’s unique ecology, from its pristine air to its imposing landscape. Of course, the lecturer, Professor Alan Braddock, touched upon climate change and how depictions of Monhegan could start to transform.

With two contrasting examples, Braddock posed to the audience an interesting question. Monet loved painting London’s fog, but one could argue he was beautifying smog from the Industrial Revolution. Do artists have a responsibility to vilify the terrible impact humans have on the planet, like in George Osodi’s Oil Rich Niger Delta series?

After the lecture, I read the article on Osodi linked above, and this quote really struck me:

I had a lot of challenges on how to represent these images. Some images were so graphic, so gory, that would drive people away from the image. I realised that people love things that are beautiful- it’s easier to attract someone’s attention to something that’s beautiful […] I tried to take images that are very beautiful, and by doing so you get someone’s attention. When it comes closer, you see there is something behind the image, there’s a reason why this image was shot […] But this time it’s too late, you can’t run away from the image, because you’ve been dragged into it.

-George Osodi

Osodi’s photos are incredible. His composition is unbelievable, and he accomplishes exactly what he describes. You are first drawn in by the framing and the colors, and then you feel the heat, the pain, the exhaustion. Your brain takes a journey in just a few seconds, and you know you won’t forget that image.

Braddock also brought up Subhankar Banerjee, whose photos of Arctic landscapes stirred so much controversy on the floor of Congress that his exhibition at the Smithsonian was essentially sabotaged. It is amazing the way people freak out when realities they don’t like or acknowledge are available to the public.

Anyway, while I’m not exactly in a position to document humanitarian and/or environmental atrocities, the lecture did remind me of the power of art and photography. So, I went on a photo walk.

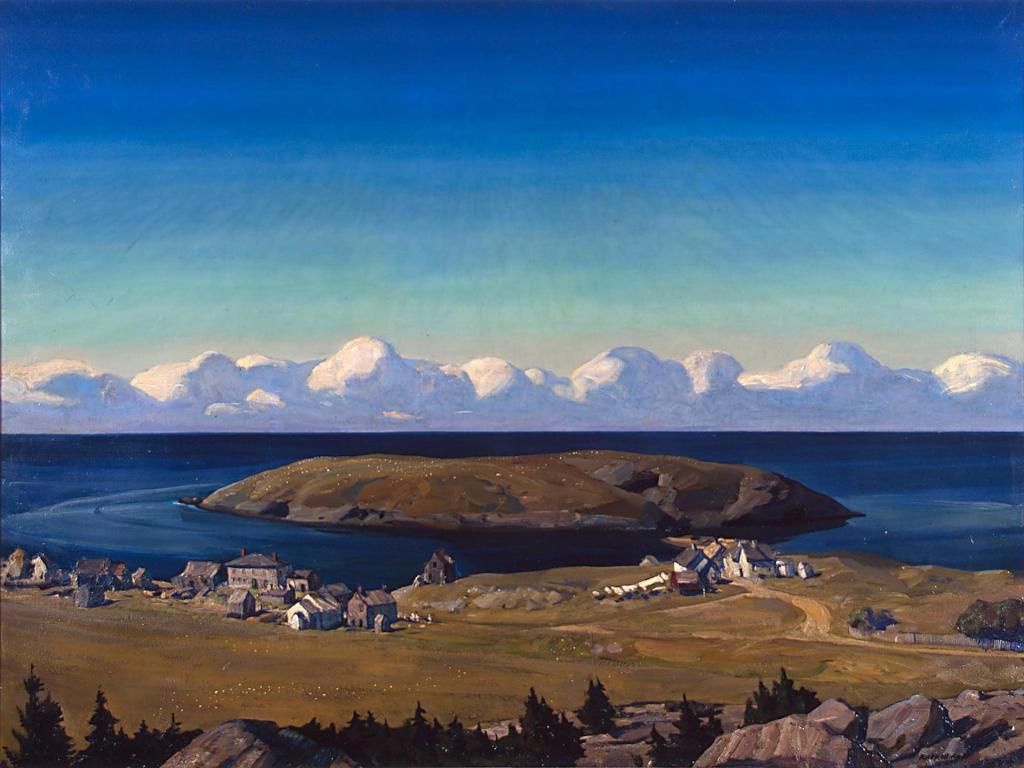

First, I walked up to the lighthouse, which I have to imagine is where Rockwell Kent was when he painted Island Village, Coast of Maine in 1909, to the left here. That was before the Inn, before the Red House, before Carina. But not before the Starling homestead, The Influence, or of course the road up to the lighthouse on the right.

Rockwell Kent’s Monhegan Island was cleared for sheep pasture; now the sheep are gone (except for on Manana Island, the smaller island seen here), but the people certainly aren’t. I love visual comparisons like this because it reminds me that this land existed far, far before me and it will (hopefully) exist for an extremely long time after me. I will be one of zillions of people to see this view. Sure, life is precious and fleeting, but it’s also so insignificant. We are here for a blip, compared to how long this land mass has been and will be here.

Deciding to go full Art Mode, I shot the rest of the photos in black and white. I learned in a photography class that shooting in black and white not only helps you use the Zone System to gauge exposure, it can also help identify the most interesting lighting in a scene.

Overall, I’m pretty happy with these. I hadn’t taken photos just for me in a while, and it was nice to capture these little moments of calm, even though I do think I scared the shit out of that young pheasant in the last one. I’d like to challenge myself to veer from my tendency to place the subject right in the middle of the frame, though. But maybe I just like the stability and balance it gives the image. My brain really doesn’t want things off-center. Something to keep thinking about.

Lots of things feel completely backwards and out of control right now. The one thing I can do, at the very least, is make some images that may help somebody (even it’s just me) get a mini-escape from the madness.